Interview about the sculpture exhibition in Valencia

A dialogue between Miriam Atienza and Arne Quinze

Miriam Atienza, Director of the City of Arts & Sciences Museum, and Arne Quinze have a talk about the new sculptures in Valencia.

Hello Arne, and thank you for coming to Valencia and to the City of Arts and Sciences. This is your first time in Valencia, and in Spain, for a big exhibition, right?

Yes, that’s true. It’s a great pleasure to be here, and in this particular setting. It’s perfectly in tune with my vision of transforming cities into open-air museums. In the museum behind you, everything is always behind closed walls, and it’s always very difficult to draw people into museums. What’s too bad

is that only a small percentage of people visit museums, and that’s a pity, because to me, this place is so magical. You have the public domain and you have the museum that is all closed up, but that is so worth discovering. I was particularly drawn to this place because it’s a place of encounters. And I think that art, and culture, can stimulate encounters. We tend to live in these compartmentalised little clubs. There is less and

less communication, even with the shift towards the internet, WhatsApp, Facebook and all that, but people still live behind their walls. Look, cities, for me, are mostly made of concrete, which is pretty grey, pretty sober, pretty mono-cultural, but what I’m trying to do here, with my sculptures, is plant these flowers that are shooting up in this concrete world.

What was your reason for coming here, and did you make these sculptures especially for this space? What prompted you to come? It’s really a pleasure to have you with us.

First, my overriding personal goal is to transform cities into open-air museums, and my second goal is to create cities that have the same diversity as nature, and the same balance, because all of my work is based on nature. When you look at the space here, which is a very unique space, Calatrava has created a city within a city, and he has also created a space conducive to encounters. And that is what was enormously attractive to me, with people increasingly living cooped up inside, there is less and less physical contact, despite the huge amount of contact through social media, but I believe that we are still living in the heritage of the great visionaries, or non-visionaries, who built cities in the 80s and 90s. The thing is that cities have become very inhuman, and places like this make cities more human, because people meet each other. And I believe that my work, what drives me in fact, is to render the beauty of nature without actually rendering nature itself. My work is based on beauty, on the optimistic side of life, I am very optimistic, that’s why I use these colours.

We can’t avoid the fact that climate change is happening, the waters are rising but then you have droughts, the planet is dying. With climate change, we always show the negative side. I try to show people the beauty of nature so that they realise that we must do everything possible to preserve it. Our cities are built in such an inhuman way that public spaces have become concrete; they are ugly. My big dream is to transform these public domains, by drawing on culture and on nature. Since I was born in 1971, man has destroyed more than 30% of the flora and fauna, which is why it’s so important to show the beauty of nature through the beauty of my sculptures. That idea runs through my work. Often, when we speak of cities or climate change, we adopt a negative perspective. For me it’s the opposite; I want to show the positive side through my forms, through colours, so that people will see that nature has such beauty that we must preserve it, that we must do something. I believe that if we change our public spaces into better places, more human, more natural places, we will bring out the humanity of cities. I think that’s really important for the future.

I would like to know what you set out to do here. You’ve created different types of sculptures. How did you decide what you were going to do here?

When I came here, it brought back a memory of a long trip to Iceland. When you travel across Iceland, there are all these volcanic mountains, and they’re black. For days and days we travelled across this black landscape, and the first signs of life that we saw were these little flowers, pushing up through the black lava. When I was here it was the opposite; everything is white, everything is beautiful, everything is clean-cut, and I thought about my flowers, I wanted to make organic flowers bloom here, colourful but nevertheless with a certain power. After all, nature has enormous power, and I wanted people to see, through my sculptures, the duality of nature, its fragility and its extreme power. When you look at the sculptures they could almost be made of paper, but they are made of aluminium, and to create them we used a big crane to bend them, and you feel the power that they exude.

That was my reaction, there is this enormous power, and at the same time it is delicate and there is colour everywhere. In my opinion, the contrast you’ve achieved through the colour works really well.

I think that nature has colours for a reason. You see it in fruit; they are full of attractive colours so that we’re tempted to eat them. In nature, there are colours that are made to attract, but also colours made to frighten. The beauty

that we see among the animals, the play of colours, is very interesting, and it’s something we tend to forget. I believe that we need colours in cities. Cities have become very monotone, and wherever there is colour, people smile a little more, they feel more relaxed. And I believe that it’s important to encourage this way of thinking; I hope that visitors, when they see these installations, think along those lines. That is the little seed that I am planting in their heads, and I hope that a lot of ideas will grow from that seed.

Here, we are in a public space, and yet there are so many visitors who come here who often don’t even venture into the museums; they just wander about. I think that it’s important to provide free access to things on the outside, to draw people’s attention so that they go inside the museums. And I believe that, thanks to what you are doing, we can draw visitors’ attention.

It is so important because it really is too bad that only a small percentage of people visit museums and yet culture is one of the best ways of broadening our minds. And I believe that without this education, we’re gearing ourselves up for a very dull life, a negative kind of existence. We need this in our education, and museums have a very important role to play.

But museums are always hidden behind these four big walls and these little doors. And sometimes it’s difficult to push open those doors. My great mission in life is to transform public spaces into cultural spaces, where we can exchange ideas, even if the artist isn’t your cup of tea.

We artists aren’t here to make sculptures that everyone likes, but from such time as it triggers a conversation, a discussion, we’ve achieved our mission. I hope that, through these installations that we’ve placed here, people will be more interested in coming to see what’s happening inside.

I think that this is one of the duties of museums, to break out of their walls, to go back into the cities. They shouldn’t wait for the people to come to them, but rather they themselves have to go out and find the people; they are the ones who should be injecting culture into cities. That is so important.

We have the museum of science, which is interactive, and if you grab the attention of someone who goes on to touch something, he will experiment with that thing. With sculptures as well, you can provoke emotions - if, in the museum of science, you can attract attention in that way, with art, you can trigger this reaction in the person as well.

I got the inspiration to get where I am today when I was fifteen years old. I lived in Brussels, which in the 80s was such a grey and sad city, and they had built

a new underground station. I remember going into the tunnels on the day and night before they opened the underground station. There was the train, the carriages, all nice and shiny and new, but very grey. I painted the whole thing, from beginning to end, with plenty of colour. The next day, the day of the opening, the train came into the station. All the officials were there, the ministers, the mayor, the politicians, to cut the ribbon, and there was the train, full of colours. A lot of people said it was pretty, and there was something jolly about it. Others said it was horrible, that it was vandalism, a massacre.

I was there in the crowd, with my hands still covered in paint, hidden in my pockets. There was something magical about what happened there, the people who loved it and who didn’t love it at all were all talking to each other, all communicating. There was an energy going through there. And when I saw that, I told myself, that is what I want to do, I’m going to make people communicate through art. And after my graffiti, I very quickly came to understand that I wanted to change public spaces with my big sculptures, and if that creates an emotion, if it draws people in, if they talk to each other, then we, the creators, have won.

How did you become an artist? Because of things like that, or were you born this way?

I was born like this. Being an artist isn’t a choice, you either are one or you’re not, it’s something that flows in your veins, it’s something that is there, that is present, that we cannot escape, and that has to come out. With some, it comes out more than others, but for me, it’s my life, my passion.

I was wondering whether the artist is an instrument to bring out the art that people need at a certain moment, at this point in time, because each era has a different idea of art, or it is just a question of the artist doing what he likes, which has nothing to do with what is going on around him. What’s your take on that?

I believe that there are two things. First of all, I make art because I have it under my skin, and it has to come out. Secondly, I am truly a child of the planet. My great passion is nature, my flowers; around my house. I’ve planted more than 6,000 flowers and plants, just to study them to know how to create the sculptures that I make today, but I also have to send a message to politicians with my work. I hope that today’s politicians won’t go down in history as the ones that destroyed the planet. With my art, I want to show the beauty of nature, to make them aware that if they don’t take very concrete and dramatic steps, we will remember them as the politicians that destroyed the planet. I try to create a positive dialogue through this work; that is my personal mission. If we have no more planet, there won’t be any more point making art.

You could say that you are an instrument to bring out what we need right now.

I do see myself as an instrument, but I miss the romantic side of cities. Before, romanticism was a good thing, it was pretty, it was joyous, it was romantic. And today we hardly have any more of this romance. Everything has become superficial. I believe we need romanticism in our lives. We need this nature, this balance.

Active romanticism, not passive?

Active romanticism. I believe that I am there to fight, absolutely!

In a certain sense I am a romantic: the quest for nature in painting takes me a bit closer to the ideas of Romanticism, which in our contemporary towns and cities have been completely lost. What is more, the romanticists turned against industry, which was making its appearance at that time, and also technology and the cities. Places that had not yet been ‘defiled’ were called ‘nature’, and that’s what they glorified. For example, like me the romanticists also very much appreciated the ‘wilderness’, because they supposed that that was where the purest, most authentic form of nature was to be found. They also assumed there was a unity between man and nature. They found this unity in the countryside. I am also looking for that sort of harmony, but for me the contrast doesn’t have to be so sharp. We need green and open space and living in towns and cities is actually good for that. I believe we can solve a lot in cities if we apply the right dose of Romanticism, greenery and culture. Integration would go considerably more smoothly and the cities would become substantially more human. Every beautiful place automatically attracts beauty and is more easily maintained and brings people together. Public spaces should be better and more agreeable than our own living rooms, but our towns and cities are still a million miles from achieving that.

It is striking how the colours of the sculptures interact with their organic forms. They enter into dialogue with their surroundings and are clearly predestined to be located here. Does colour play the same role in your paintings?

There isn’t really any boundary between my paintings and my sculptures. Despite my sympathy for the ideas behind the art of Romanticism, it is still too clearly delineated for me and in my paintings it is the impressionists who attract me more. They are

a great example to me. In terms of technique, the impressionists were most striking for their handling of contrast. They painted with colour and light. It was not a question of the reality, but of the impression made on them by the subject they were painting. They devoted particular attention to the various shades of changing light and the interplay of colour values. They often used complementary tones on a finely gradated scale from light to dark. Forms and outlines were actually subordinate to the impression.

Claude Monet, Cézanne, Pierre- Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas and all the rest. They usually painted more or less ordinary scenes, but what mainly attracts my attention are the landscapes and nature. The colours of my sculptures are just as much my impression of nature as their forms are. But abstract.

And in fact the sculptures lean slightly more towards Surrealism. The surrealist artists also depicted an impression or a feeling, but rather of something imaginary or something abstract. After all, Surrealism didn’t originate in painting, but in the literary world. Putting a way of thinking down on paper, without restriction and free from moral values. In painting, these fantasies were often rendered in a hyper-realistic manner; you only have to think of Magritte, who combined completely incompatible or, at the very least, unexpected images. But it was equally possible for the works

to be entirely abstract, as in the case of Hans Arp. You also see abstraction in the work of Joan Miró; it’s recognisable, but definitely not realistic.

In my imagination I see absolute beauty. And I try to convey it. Surrealists also try as far as possible to give their imagination free rein. For example, they paint dream images, things that don’t exist. Automatic drawing is in fact also a way of showing your fantasies. Surrealism is not an aesthetic school or style, and you can’t see any real uniformity in all the works, whereas you do among the impressionists. It was an intellectual movement, an idea that led to what is called form I can identify with.

So as far as my sculptures are concerned, I find Surrealism very appealing. It represents absolute freedom. I like making things that lead me to absolute freedom. Once again, a part of it is extremely abstract and part of the image has to be filled in by the viewer’s imagination. From Max Ernst to Miro to Willem de Kooning, who was ultimately counted among the ‘abstract impressionists’. They are my great mentors.

When you set out to make them, do you have an idea of how they’re going to turn out, or is it a gradual evolution? How does the process of the sculptures’ creation work?

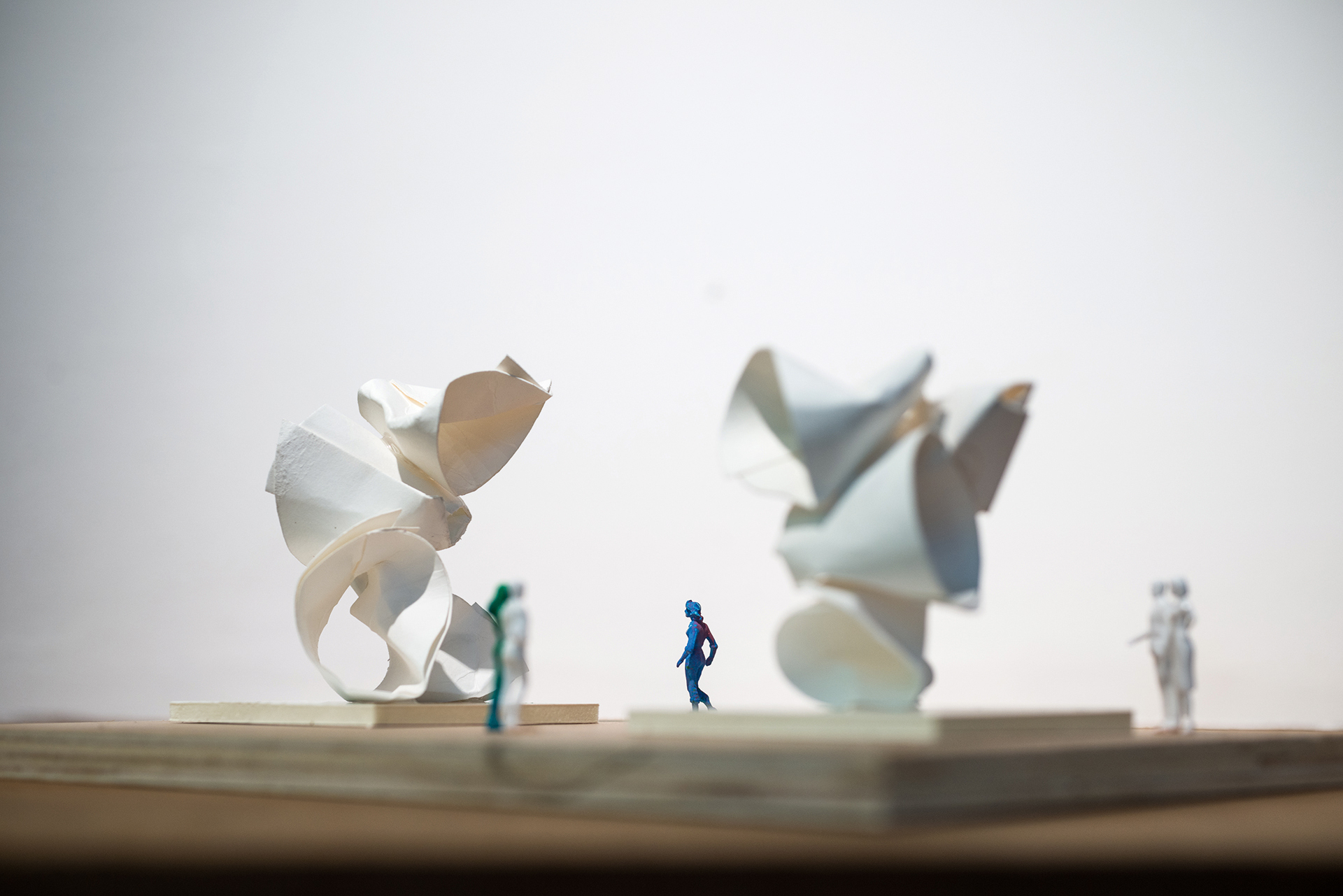

My work is an evolution that never stops. It evolves constantly, but what you see behind us is a study that was made over years to get to this point. Beforehand, I do a lot of research through my plants, through the architecture and chemistry of plants, through their energy, through the physical side. Nature is a life with extremes that take off in every direction. When you study that, you step into a world that is absolutely marvellous. But before getting to that point, there is a lot of drawing, a lot of mock-ups, a long search that helps me to create what you see before you here.

You decide whether you will make it out of wood, or steel, or aluminium. For the production process, you have an idea, but afterwards it must be transformed, must be created.

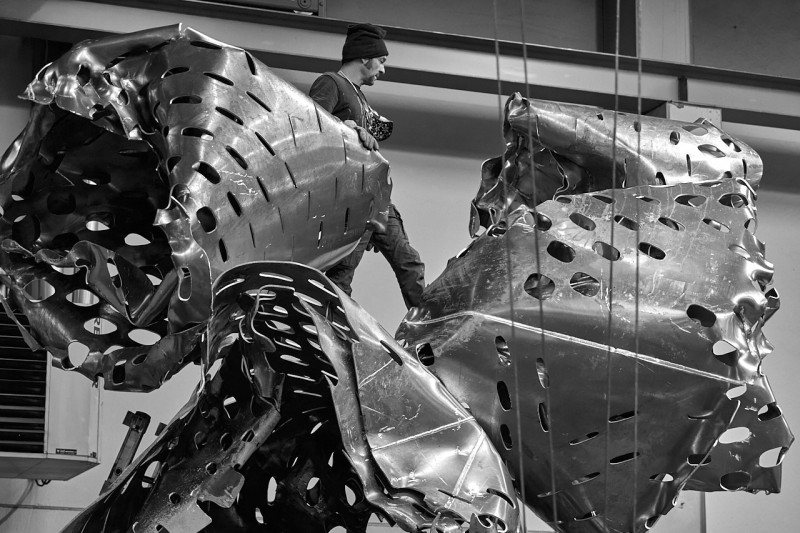

I choose aluminium and steel as materials because they allow me to create forms, toys, with this brute force when I deform them, when I fold them, when I weld them, when I cut them. For me these are materials that help me to translate what I have in mind. Even before knowing how to do that, I have 25 years of experience to draw on, I’ve played with materials and haven’t stopped evolving. Experience helps me, but it’s above all the possibility of opening my eyes, of looking around me, of observing and absorbing the things that go on around me.

During the installation of the sculptures at the City of Arts and Sciences Museum.Valencia, February 2019.

Do you think that life belongs to us, or is it more us who belong to life? That we are part of the earth, but does the earth belong to us?

Just like with climate change, there are always things that we do that are bad for the earth and for nature. I believe that we are the only living species that gives nothing, that only takes. We take, and leave nothing in place of what we take. We are busy consuming the planet, and we are close to passing the limit of consumption. I believe that if we continue on this path we will end up destroying ourselves. But it’s refreshing to see the mentality of the young, to see that things are starting to change. So I hope that the youth are our future. I have a pretty negative vision, but I remain positive nonetheless; I believe that, at a given moment, the planet will do a big clean-up, and those who want to survive will survive. That is already happening today, it is already going on, and I believe that we are only at the beginning of the problems. At the beginning of the transformation of the planet. I remain optimistic when I hear children talk. They are much more concerned with the planet than we are. Our generation, and that of our parents, we were not aware. Today it is so important that we become aware, and I hope that the next generation will save us.

To wrap up, I hope that this will be a success, and I hope that we will succeed in knowing and seeing that people can change, and I also hope that you will be satisfied. Was it a challenge for you to do this exhibition? Was it a challenge to come here? What did it mean for you?

It was a challenge, because normally I tend to create large- scale installations, and here it was the opposite because there is an enormous competition in this environment, just look at Calatrava’s work, which is superb, and exudes an incredible power. The challenge was not to pit myself against this architectural power, but rather to play with it. I believe that just by creating something this small, and my sculptures aren’t particularly small, they are six or seven metres high, I believe that there is a balance with their environment. It’s the same with flowers. Just like a tree with flowers blossoming on it, the flowers are what make the tree more beautiful, and I hope that my flowers enhance the architecture that we see behind us.

Finally, what kind of reaction do you want to see in a passer-by who comes across your sculptures.

One thing: a smile.

Creation process

How I assemble the cones of the Lupine

A step in the creation process of a Lupine sculpture. During this process you can see an amazing...

Behind the scenes of the metalworking studio

The creation of Mono No Aware

Over the past few days, Arne Quinze has hidden himself again in the metalworking studio to...

People braving storm Ciara

Storm Ciara seen from a Rock Strangers perspective

Ostend, February 10th 2020. Many people are attracted by the spectacle of the sea in combination...